Other typographies: reshaping language from distinct perspectives

Kylièn Bergh

Every language is shaped by conventions. So is the reproduction of our language, via designed letterforms and typographic compositions, charged with all sorts of norms. Only by sticking to expectations can, for instance, an ‘A’ be understood as a letter and a carrier of meaning. But who is actually involved in upholding these conventions and what do these norms say about the scope and use of our language? Until recently, typography was largely the domain of skilled male professionals—maintaining control over the profession by gatekeeping and fostering norms, which consequentially may lead to homogeneity in typographic practices. However, the emancipation of women throughout the twentieth brought about changes, integrating female practitioners into design practices. Even more so, the widespread accessibility of software has liberated design practices from expert knowledge, making it possible for anyone to access and use designer tools. So, how do these developments affect societal norms prevalent in the visual reproduction of our language? Or, specifically, what is the role of female practitioners, the identity of the maker, and feminist perspectives in confirming or rejecting homogeneous conventions?

Distinct perspectives: women in graphic design

Historically, women practitioners occupy a controversial position in design. Integral to design – and the underpinning modern movement in general – is the division of labour with as consequence assuming and appointing women roles outside of professional practices and in foremost domestic environments, as design historian Judy Attfield points out.[i] Crucial to recognise, according to Attfield, is that women experience the world differently from men and hence should be taking part in the processes shaping our everyday lived environment. “The role of design in forming our ideas about gender power relations often remains invisible,” as Attfield writes, “while at the same time it makes them concrete in the everyday world of material goods.”[ii] Thus, examining design through a feminist perspective reveals the relevancy of rethinking who is engaged in design disciplines, as much as who it is designed for, and to rethink the power structures upholding arbitrary gender divisions.

In addition, exploring design through a feminist perspective exposes the power structures in place upholding arbitrary divisions. That such form of gatekeeping is of effect in our typographic practices – occupied with the reproduction of language – is exemplified by the design collective MMS. In Natural Enemies of Books: A Messy History of Women in Printing and Typography (2020) graphic designers Maryam Fanni, Matilda Flodmark and Sara Kaaman in develop an assembly of testimonies, pointing out how women in the early twentieth century were excluded from typophiles clubs. Excluding female practitioners and enthusiasts from professional associations consequently resulted in keeping them from hearing about job openings and, hence, integrating in the profession.[iii]

Nevertheless, women have been active in every aspect of design and involved in production, as much as in consumption, reflection, historicization and curation.[iv] In a pinnacle dissertation on the role of women in design, art historian Marjan Groot demonstrates how female practitioners contributed to applied arts and design from the turn of the twentieth century onwards; showcasing an array of graphic designers including Gerarda de Lang, Cecile van Grieken, Willemina Polenaar, Annie Tollenaar-Ermeling, Julie de Graag, Emilie van Kerckhoff, Anna Sipkema, Nelly Honing and Rie Cramer.[v]

![blad [calendar page with daffodils for April, titled ‘Flower and leaf], ca. 1904, colour lithography on paper, 250 mm x 307 mm, Collectie Rijksmuseum, https://id.rijksmuseum.nl/200295875.](https://wimcrouwelinstituut.nl/media/pages/research/other-typographies-reshaping/979925d72b-1750423718/image_01-1500x.jpg)

Netty van der Waarden [design], Gebroeders Braakensiek [printer], C.A.J. van Dishoeck [publisher], Bloem en blad [calendar page with border decoration of thistles, titled ‘Flower and leaf], ca. 1900-1910, colour lithography on paper, 250 mm x 307 mm, Collectie Rijksmuseum, https://id.rijksmuseum.nl/200817234.

Despite being involved in design, however, women are often overlooked or undervalued due to favouring male pioneers, as also design historians Frederike Huygen and Cheryl Buckly separately point out.[vi] “These methods,” Buckly writes, “which involve the selection, classification, and prioritization of types of design, categories of designers, distinct styles and movements, and different modes of production, are inherently biased against women and, in effect, serve to exclude them from history.” [vii] Even more so, Aasawari Kulkarni and Alison Place describe these procedures of prioritization and glorifications in typographic practices as typatriarchy: making explicit how patriarchal power structures institutionally uphold gender inequalities.[viii] It is within patriarchal cultures that women are more inclined into supportive and subordinate roles – often working without recognition – and thereby getting overlooked, as historian Frederike Huygen points out in reference to Briar Levit’s Baseline Shift: Untold Stories of Women in Graphic Design History (2021).[ix] Thus, as Alison Place writes:

“Feminism is not just about gender; it is about power. When viewed through a feminist lens, the trouble with design is not simply a matter of unintended consequences–it is a matter of ingrained power structures that influence design’s methods and dictate its impact.”[x]

Feminism, thus, has not only brought about a wave of emancipation but also a lens to critically examine unequal power structures and the traces of gender divisions in cultural conventions or practices.

Distinct perspectives: a question of identity

Approaching designers on the basis of their gender identity, however, also comes with underpinning issues. First, when approaching female design practices, distinctions are inevitably made on the basis of gender and sex. Whereas recognising one’s gender identity in rectifying the patriarchal disbalance might be relevant to some, other practitioners may reject such a standpoint and rather be seen as part of the professional field regardless of their gender identity.[xi] As Huygen writes: “Viewing female designers as women means limiting the gaze to their sex and gender.”[xii]

Second, allowing the identity of the maker to inform the design process is in itself a controversial subject in design discourse. A lineage of design history is overflown with contrasting figures, stating that the designer should take part in the communication and present as expression of subjectivity or, in contrast, absent in subjecting oneself to servitude. So, how important is it for the designer to recognise individual identity, and what is the role of the designer’s identity in communicative practices?

Foremost, type design and typography should be seen as communicative practices, hence, involved in the representation and reproduction of language. It is primarily through language that we find the means to express ourselves. In doing so, we allow ourselves to interact with others in the exchange of information and mediation of ideas – facilitating mediations between the plurality of people.[xiii] This suggests an intimate connection between language and our sense of self. “Only through acting and speaking can we show to the world who we really are in our unique personal identity” as João Vila-Chã writes.[xiv] The reverse seems equally true. While utilising language to express ourselves, it also seems that we need a sense of self to utilise language. Described as ethos in rhetoric, the character of the orator testifies the credibility, authority, and morality of communication. Hence, making the identity of the designer explicit in the expression can be used as means to reach out to others.

The identity of the designer is, thus, not about ego but indicative of interpersonal relationships. Even more so, as graphic designers Johanna Ehde & Elisabeth Rafstedt argue, recognising the identity of the designer is a form of integrity to labour conditions and interrelatedness.[xv] Throughout the working process, the designer makes all sorts of choices. Inevitably, such choices reflect individual ideas of the maker as much as it leaves traces of the working processes. Erasing such traces – as is often aimed for in modernist and minimalist approaches to design – consequently erases traces of human involvement in the labour efforts. What emerges is a degree of alienation. Embracing the traces of individual craft, on the other hand, becomes the means to signal human involvement. In other words, articulating identity is a matter of interrelatedness and integrity.

Thus, expressing identity serves not only as a personal statement but also as a manner to reach out to like-minded individuals, sharing similar worldviews, values, cultural norms, or aesthetic sensibilities. Like so, the visual articulation of identity can be more than merely targeting audiences and, instead, contribute to shaping communal ties. This is exemplified by the Rietlanden Women’s Office, Céline Hurka and Xiaoyuan Gao – panellists of the It’s All Graphic discussion on expanding the field of typography – who are all involved in the organising of events; fostering collaborations, hosting poetry readings, organising lectures and facilitating participatory workshops. This reinforces the focus for designers to foster networks and relations.

Distinct perspectives: questioning norms

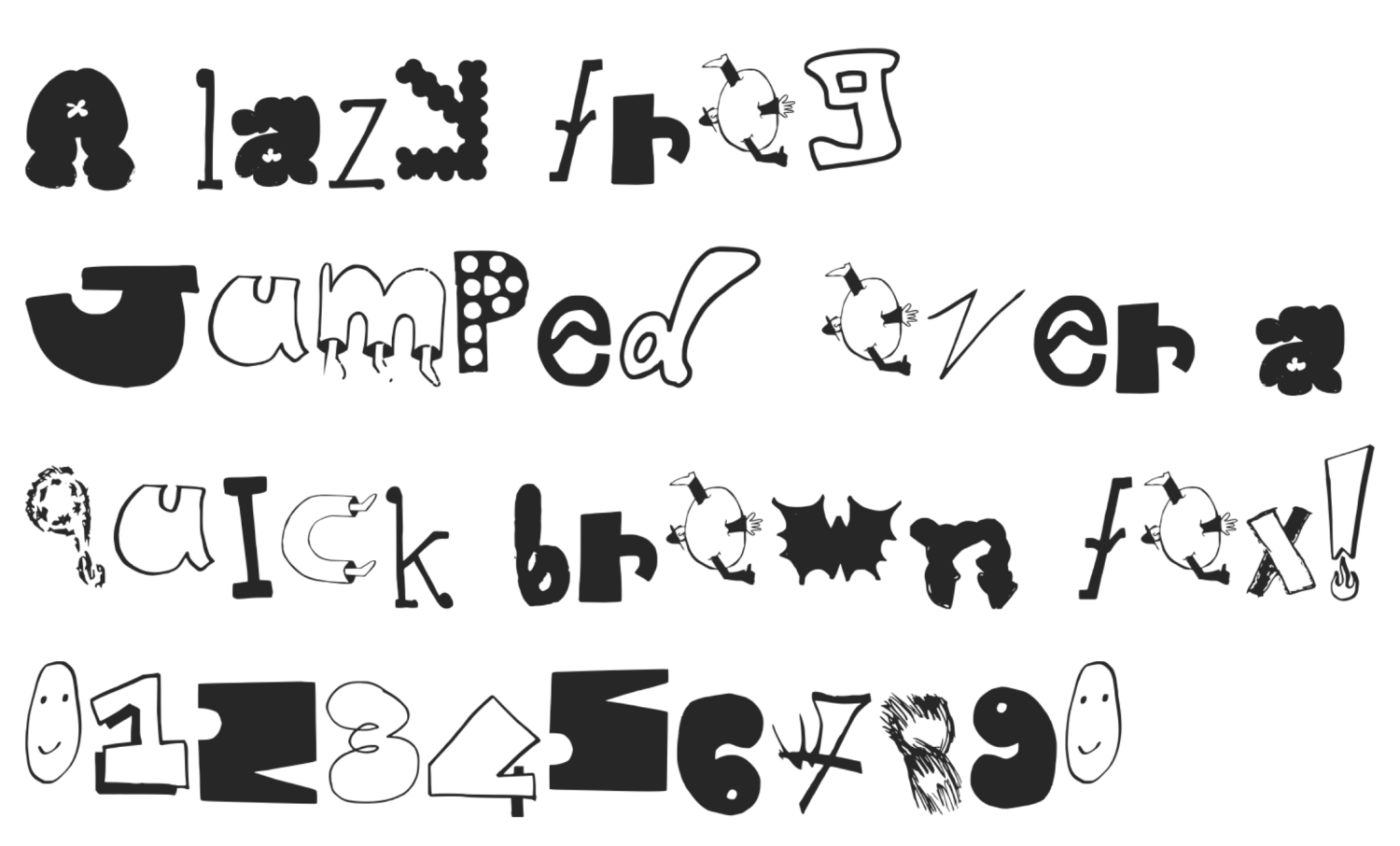

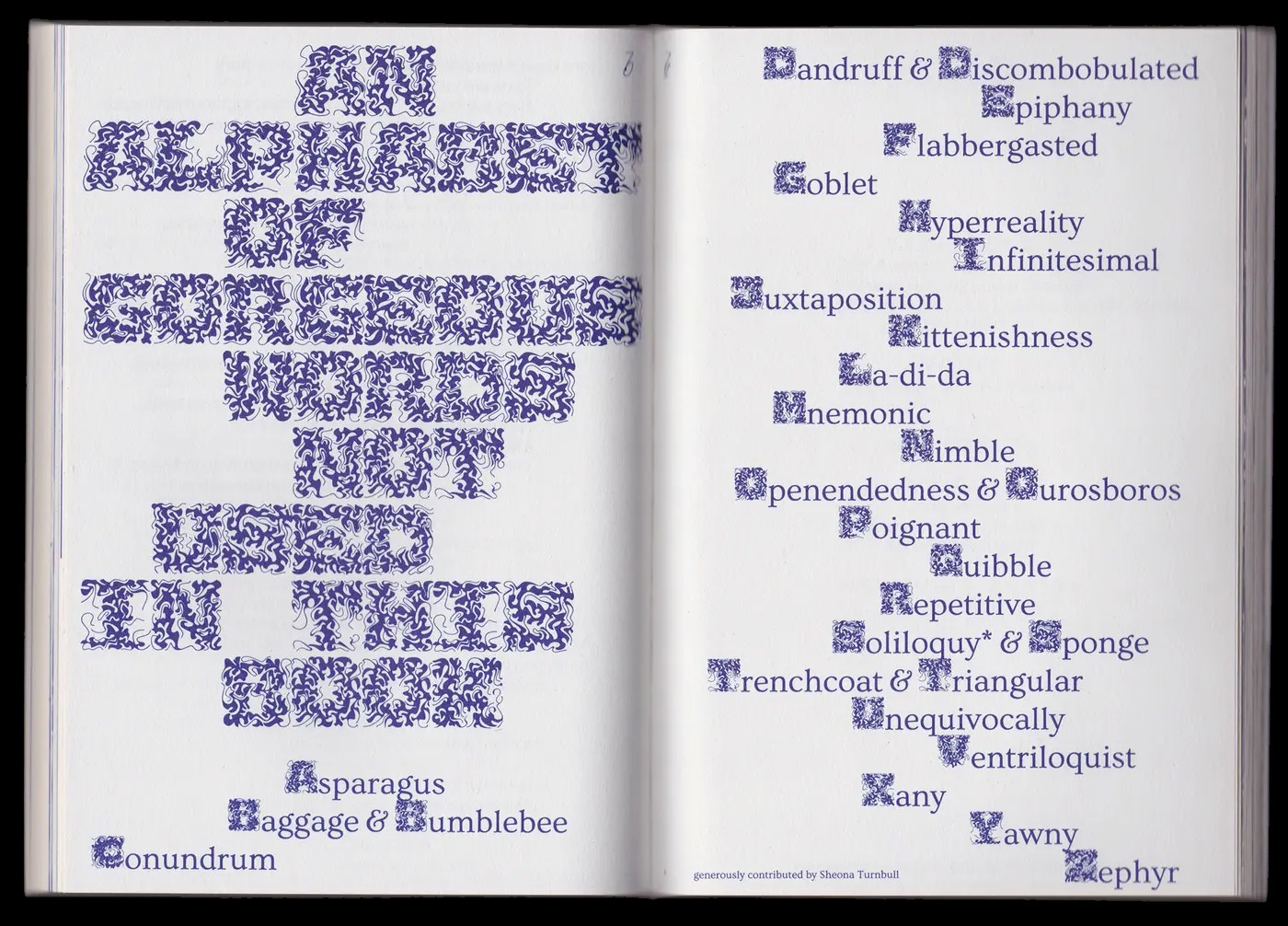

Letting the identity of the maker shine through in the design undoubtedly affects the outcome of the work. Arguably it comes with aesthetics that deviates from normative styles – dictated by the visual language of corporate capitalism in which personality is subjected to professionalism.[xvi] The rejection of corporate aesthetic conceptions is, herein, not primarily a stylistic concern but a synthesis of personal and political ideals into professional practices. Even more so, challenging the homogeneous and normative nature of conventions also expands the range of how we can express ourselves through typographic articulation.[xvii]

That such questioning of conventions comes at a price of legibility can be taken for granted as collateral damage. In fact, increasing the difficulty of digesting information can even be used to invite more active interpretation. As Johanna Ehde & Elisabeth Rafstedt point out, we tend to read whatever we read most.[xviii] Hence, imposing challenges to the reading may aid bypassing biases: steering towards more thorough comprehension.

Even more so, embracing human relationships and interrelatedness can even help to redirect graphic design and type design to more compassionate communicative practices. As underpinned by Céline Hurka, listening is a crucial component of design practices.[xix] It is compassionate listening to others which allows to synthesise different entities and identities into a shared form of expression. The identity of the designer, herewith, is not a static or a given but in constant flux with sensibilities to other collaborators. It is from this compassionate coalescence that unique visual languages may emerge, facilitating the mediation between the plurality of people. Thus, allowing personality to seep through into visual language paves the way for subjectivity, hence, a rather personal and intimate form of visual communication.

Lastly, fostering compassionate communication also comes with specific attention to the dissemination of the work. Design does not stop at the delivery of a product but also should consider its afterlife, hence, what happens after the work moves beyond the maker’s reach. Particularly to type designers it raises the question, what happens when a font is released? For what purpose will it be used, and by whom?

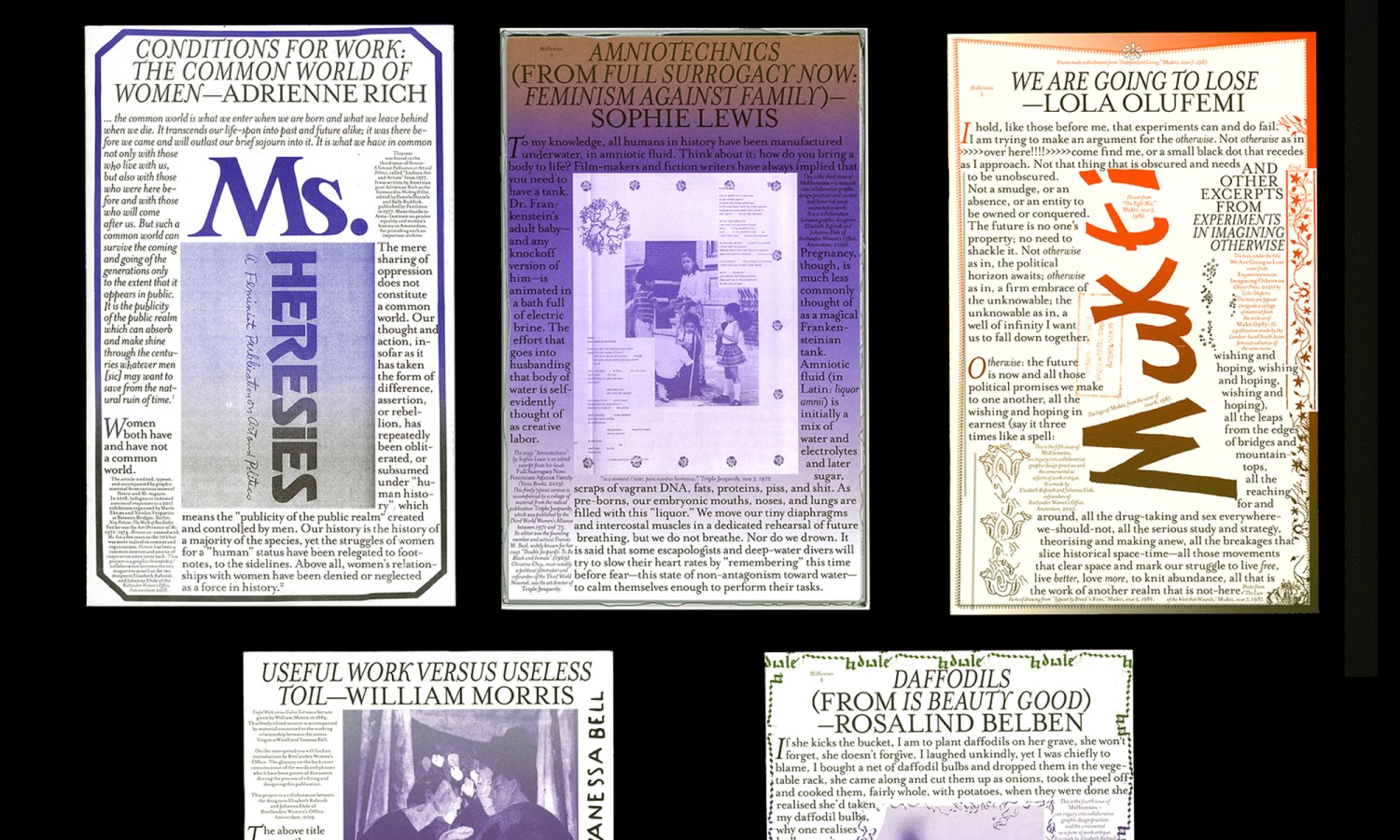

Aiming to stimulate certain use of her type design, Céline Hurka embraces her identity by taking on a feminine persona – supported by actively seeking out specific collaborations – as means to foster the usage of her work by like-minded people. In addition, even licensing is used in restricting the fonts from inappropriate use for harmful expressions, including racism. Similarly, Rietlanden Women’s Office purposefully rejected using barcodes, for the publication series MsHeresies, in avoiding the offspring of their labour to be retailed and distributed by controversial corporations. Such pragmatic decisions, concerned with the dissemination of their work, place conscious restrictions on who benefits from the designer’s effort. This can also be seen in the efforts of the notyourtype foundry, initiated by Xiaoyuan Gao, focussing on distributing tools and typefaces from BIPOC and FLINTA* designers. Whereas once the design profession revolved around exclusive access to, and expert knowledge of tools, we now see a role for designers emerging to open up production processes, providing access to tools and facilitating, therewith, opportunities to articulate oneself in a public domain.

Conclusion

To conclude, examining typographic practices through a feminist lens reveals how deeply gendered power structures have shaped — and continue to shape — the visual reproduction of language. Once the domain of male experts, type design and typography have the potential to redirect to more compassionate forms of communication and distribute the access to tools. Yet access alone does not guarantee equity; enduring structures of canonization, or typatriarchy, continue to marginalize the contributions of women and other underrepresented groups. Allowing a sense of self to be part of a communicative expression is integral to establishing connections with others. What has emerged is a sentiment in favour of allowing the identity of the maker to inform the method and outcome of design processes. This is not restricted to aesthetics, but also concerned with the dissemination of the work: fostering reciprocal collaborations and community bonds. Recognizing the identity of the maker is thus a critical act — not as a celebration of ego, but as a reaffirmation of labour, integrity, and interrelatedness. Feminist approaches to design invite a rethinking of not just who creates, but for whom and to what end. By embracing subjectivity and fostering compassionate communication, contemporary practitioners challenge normative conventions, paving the way for more diverse, ethical, and interconnected visual languages — reflecting the plurality of people that constitute our societies.

_______

Kylièn Sarino Bergh is fellow at the Wim Crouwel Institute in Amsterdam (NL) and lecturer histories and theories of graphic design at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague, the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam and the University of Amsterdam. Together with Richard Niessen he teaches the master program ‘Graphic Design as a Mediator in Public Space’ at UvA.

_______

This article expands on the panel discussion It’s All Graphic: Other typographies, organised by the Wim Crouwel Institute on the 3rd of June 2025 and hosted by Pakhuis de Zwijger in Amsterdam. During the event graphic designers Johanna Ehde & Elisabeth Rafstedt, founders of Rietlanden Women’s Office, and type designers Céline Hurka and Xiaoyuan Gao, founder of notyourtype foundry, engaged in a discussion expanding the field of typography and type design, moderated by Elisabeth Klement and Kylièn Bergh.

Notes

[i] Judy Attfield, "Form/Female Follows Function/Male: Feminist Critiques of Design," in Design History and the History of Design, ed. John A. Walker (London: Pluto, 1989), 200.

[ii] Ibid., 203.

[iii] Fanni, Matilda Foldmark, and Sara Kaaman. Natural Enemies of Books: A Messy History of Women in Printing and Typography (London: Occasional Papers, 2020), 43.

[iv] The fact that women have actively contributed to design practices is pointed out by Cheryl Buckly in the pinnacle essay ‘Made in Patriarchy’, published in Design Issues in 1986, and is exemplified in the exhibition Here We Are! Women in Design 1900 – Today at the Design Museum Brussels, curated by Susanne Graner, Viviane Stappmanns and Nina Steinmüller from the Vitra Design Museum. Furthermore, the understanding of how women contributed to design within a Dutch context, owes much to the major historical contribution of the dissertation by Marjan Groot, Vrouwen in de Vormgeving in Nederland 1880–1940, published in 2007.

[v] Marjan Groot, Vrouwen in De Vormgeving in Nederland, 1880-1940 (Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 2007).

[vi] Frederike Huygen "Vrouwen in De Grafische Vormgeving." Design geschiedenis, May 2022, https://www.designhistory.nl/2022/vrouwen-in-de-grafische-vormgeving/.

[vii] Cheryl Buckley, "Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design." Design Issues 3, no. 2 (1986), 3.

[viii] Alison Place, ed. Feminist Designer: On the Personal and the Political in Design (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2023), 34-39.

[ix] Huygen "Vrouwen in De Grafische Vormgeving."

[x] Place, Feminist Designer, 7.

[xi] Huygen "Vrouwen in De Grafische Vormgeving."

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] The framing of language as mediation between the plurality of people lends from Hannah Arendt’s emphasises on speech as the essential means of human interrelatedness. The discussion on speech from The Human Condition (1958), and other philosophical insights from Arendt, are brought in relation to graphic design in the conference paper ““Disillusionment in Dark Times: Cultivating Compassionate Communication Design Through an Arendtian Lexicon” presented at the Designa International Conference on Design Research in 2024.

[xiv] Vila-Chã, João J. "The Plurality of Action: Hannah Arendt and the Human Condition." Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia 50, no. 1/3 (1994): 479.

[xv] Johanna Ehde & Elisabeth Rafstedt, “Other Typographies: Reshaping language from distinct perspectives,” It’s All Graphic 13 (lecture and panel discussion, Wim Crouwel Institute, Pakhuis de Zwijger, June 3, 2025).

[xvi] How professionalism affects communicative practices is aptly discussed in the paper presented at the Designa International Conference on Design Research centered on the subject of design citizenship.

[xvii] See, for example, how artist and educator Paul Soulellis is seeking queer typography in aim of deviating from normative restrictions on language and its reproduction. https://soulellis.com/writing/tdc2021/

[xviii] Johanna Ehde & Elisabeth Rafstedt, “Other Typographies: Reshaping language from distinct perspectives,” It’s All Graphic 13 (lecture and panel discussion, Wim Crouwel Institute, Pakhuis de Zwijger, June 3, 2025).

[xix] Céline Hurka, “Other Typographies: Reshaping language from distinct perspectives,” It’s All Graphic 13 (lecture and panel discussion, Wim Crouwel Institute, Pakhuis de Zwijger, June 3, 2025).

Cited works and further reading

Attfield, Judy. "Form/Female Follows Function/Male: Feminist Critiques of Design." In Design History and the History of Design, edited by John A. Walker, 199-255. London: Pluto, 1989.

Bergh, Kylièn. “Disillusionment in Dark Times: Cultivating Compassionate Communication Design Through an Arendtian Lexicon.” Paper presented at Designa International Conference on Design Research, UBI, Covilhã, Portugal, October 2024.

Buckley, Cheryl. "Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design." Design Issues 3, no. 2 (1986): 3-14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511480.

Fanni, Maryam, Matilda Foldmark, and Sara Kaaman. Natural Enemies of Books: A Messy History of Women in Printing and Typography. London: Occasional Papers, 2020.

Groot, Marjan. Vrouwen in De Vormgeving in Nederland, 1880-1940. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 2007.

"Vrouwen in De Grafische Vormgeving." Design geschiedenis, Updated May 2022, 2022, https://www.designhistory.nl/2022/vrouwen-in-de-grafische-vormgeving/.

Jones, Amelia. The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. London: Routledge, 2003.

Levit, Briar. Baseline Shift: Untold Stories of Women in Graphic Design History. First edition ed. Hudson, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2021.

López Barbera, Franca, Nina Paim, Briar Levit, Books Bikini, and Design Clube do Livro do. Briar Levit: On Design, Feminism, and Friendship. Marginalias. 1st edition ed. Porto, Portugal, São Paulo: Bikini Books ; Clube do Livro do Design, 2024.

Place, Alison, ed. Feminist Designer: On the Personal and the Political in Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2023.

Popova, Yulia. How Many Female Type Designers Do You Know? : I Know Many and Talked to Some! Onomatopee; 184. Eindhoven: Onomatopee Projects, 2020.

Scotford, Martha. "Messy History Vs. Neat History: Toward an Expanded View of Women in Graphic Design." Visible Language 28, no. 4 (1994): 368-88.

Soulellis, Paul. “What is queer typography?” Paper presented at Type Drives Communities Conference 2021, The Type Directors Club, New York, May 2021.